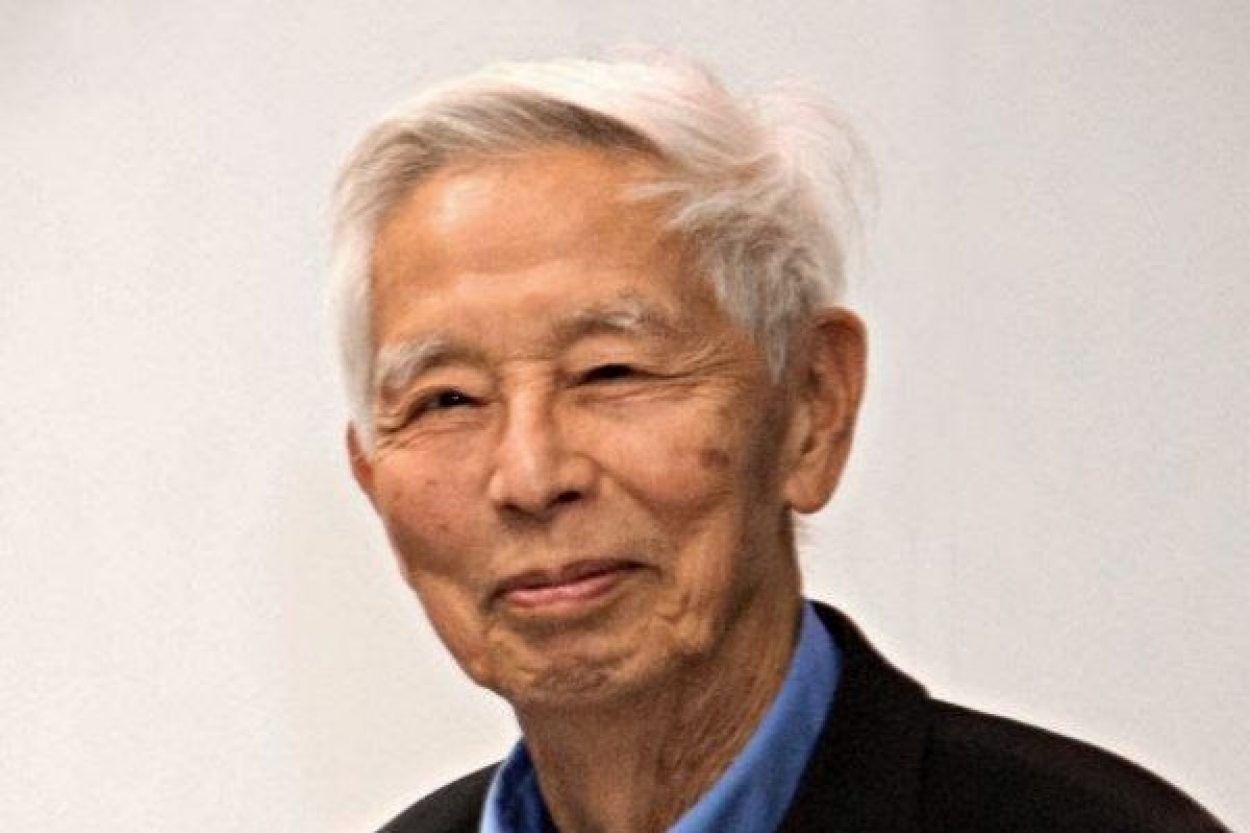

Tunney Lee, professor emeritus of urban planning and former head of the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP), passed away of complications from cancer treatment on July 2 in Boston. He was 88 years old.

An architect by training, Lee was also an accomplished planner, historian, and community activist. At MIT, his research focused on the process of community-based design, with a particular interest in high-density urban settings. He led frequent collaborations between MIT students and Boston-area neighborhoods. His approach to urban planning and architecture emphasized how these fields could be harnessed to empower and enhance the lives of people. When approaching design, Lee viewed the built environment through the lens of how individuals would construct, use, live, and interact with the creations of planners and architects.

“It’s about understanding institutions,” said Lee, when discussing community input for a series of recommendations produced by DUSP students. “You never hear any discussion as to who is going to carry out this wonderful thing we’ve just designed. That’s just of not interest to them [typical design schools]. In contrast, we would have failed if we didn’t inculcate in our students the necessity for understanding the institutional arrangements at the same time as we talk about designs.”

“Tunney was a towering, gentle, strong, font of eternally wise humanity — an ideal teacher, colleague, and friend,” says Chris Zegras, professor of mobility and urban planning and DUSP department head. “Tunney quite literally helped save Boston, Cambridge, and MIT by spearheading, against all odds, the successful battle against the Inner Belt Highway in the 1960s. That effort exemplified everything he did, combining the passion of the ‘good fight’ with the compassion of truly working with and caring for others. The outpouring of memories, from such a wide span of our community, shows how he was woven into the fabric of DUSP. We are both crushed by the loss and honored to continue working to live up to his harmonious blend of vibrancy, patience, humor, reflection, insight, and moral clarity.”

Lee immigrated to Boston from China in 1938 at the age of 7. While his father went to work in Washington, Lee remained in Boston under the care of his grandparents in Boston’s Chinatown. In an MIT Infinite History interview, Lee noted how this experience impacted his perspective of urban design.

“[Chinatown] was a classic urban village, one in which people knew each other and trusted each other and it was small,” he said. “It has certainly affected, always, my views of community, of neighborhoods, it extends all the way to my professional life, my interest in neighborhoods has always been there.”

Lee lived in Chinatown until he graduated from Boston Latin School and began his studies at the University of Michigan. After completing a degree in architecture, he worked with Buckminster Fuller and I.M. Pei. In 1970, Lee joined the DUSP faculty, earning tenure in 1977. He was promoted to full professor in 1985. At MIT, Lee supervised and read dozens of masters and doctoral theses and taught a wide range of courses, including the introductory course to Housing Community and Economic Development; Site Planning; and Planning Studio.

Lee’s colleagues remember him as a pillar of the community whose energy, curiosity, and kindness were matched by his sharp intellect, strong values, and commitment to serve voices at the margins of a city.

“Tunney was my thesis and life advisor, a force of nature, and guide to all that is good about cities and city planning,” says Dennis Frenchman, Class of 1922 Professor of Urban Design and Planning and director of the MIT Center for Real Estate. “He fought fiercely for the unheard, for his beloved Chinatown, and for all people and places in Boston that have contributed to its deep culture of grit and survival.”

Lee’s impact in the Boston area echoed beyond classes he taught and practicums he led at MIT. Lee served the Greater Boston community as the chief of planning and design for the Boston Redevelopment Authority and as deputy commissioner of the state Division of Capital and Planning Operations during Governor Michael S. Dukakis’ administration.

Lee practiced what he taught, seeking to use the tools of design to empower citizens and strengthen community-led efforts. In the 1950s, along with other urban planners, Lee provided technical assistance to neighborhood groups resisting plans for the introduction of Inner Belt, an interstate highway planned to run through Boston and Cambridge.

“It’s hard to find the words to capture the depth, breadth, and profound impact of this brilliant visionary ever committed to the good fight,” says Karilyn Crockett, a lecturer of public policy and urban planning in DUSP and the City of Boston’s first chief of equity. Crockett’s book, “People Before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making,” details this community resistance and features Lee. She writes, “[Lee] knew well the impact of a multilane highway coursing through a densely populated working-class neighborhood, and most important, he understood the relationship between highway expansion and uncatalyzed neighborhood resistance.”

Lee founded the Department of Architecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, which became the university’s School of Architecture. Lee wrote that the department’s educational philosophy needed to center on “a basic concern for the quality of people’s lives and respect for all those involved in planning and creating buildings, including the people who will inhabit the buildings, coworkers, construction workers, as well as the owners, developers, and fellow colleagues.” Today the school’s curriculum continues to reflect Lee’s values and philosophy, with an emphasis on buildings as part of the human habitat.

The City of Boston and its Chinatown remained a lifelong focal point for Lee’s efforts. Most recently, he led a collaborative project with the Chinese Historical Society of New England, the Chinatown Lantern Cultural and Educational Center, UMass Boston Institute for Asian American Studies, and many MIT alumni. The project, Boston Chinatown Atlas, seeks to understand and tell the story of Chinatown’s history, dynamics, and context, and encourage future generations to appreciate the traditions and preserve the community’s vitality.

He also led a team of MIT faculty, students, and affiliated planners, architects, and designers to develop the Density Atlas. The concept of combining the three commonly used measures of density to better understand and compare city blocks and neighborhoods emerged from a series of urban design classes that looked at housing development projects in both the United States and China.

Lee continued his tradition of public service as a board member for the South Cove Health Center; Kwong Kow Chinese School; and the Asian American Development Corporation. He was the recipient of numerous awards, including the Chinese Historical Society Sojourner Award.

“Tunney was the practical revolutionary. He didn’t shy away from the tough issues, but did so with kindness,” says Ceasar McDowell, professor of the practice of civic design and DUSP’s associate department head. “His advice through the years has served as one of my guideposts for working on the ground with communities. He will be missed by many, but will remain ever-present for those who knew him.”

Lee is survived by his daughters, Thea, Kaela, and Dara Lee Lewis; his sisters, Mu Zhen Li, Cui Yu Li, and Xiao Xia Li; and three grandchildren. The family will host an online memorial service on Sunday, July 12, from 4 to 5:30 p.m. EDT. They have also created a virtual memory book for friends and colleagues to share thoughts, stories, memories, and photos.

Donations may be made in Lee’s name to these organizations supporting his work: Asian Community Development CorporationChinese Historical Society of New EnglandBoston Chapter, NAACP2Life Communities.