When 14-year-old Jahzhia Moralez played a vocabulary game that involved jumping onto her friend like a backpack, she knew Itz’at STEAM Academy wasn’t like other schools in Belize. Transferring from a school that assigned nearly four hours of homework every night, Moralez found it strange that her first week at Itz’at was focused on having fun.

“I was very excited,” Moralez says. “I want to be an architect or a vet, and this school has the curriculum for that and other technology-based stuff.”

The name “Itz’at” translates to “wise one” in Maya, honoring the local culture that studied mathematics and astronomy for over a thousand years. Launched in September 2023, Itz’at STEAM Academy is a secondary school that prepares students between the ages of 13 and 16 to build sustainable futures for themselves and their communities, using science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM). The school’s mission is to create a diverse and inclusive community for all, especially girls, students with special educational needs, and learners from marginalized social, economic, and cultural groups.

The school’s launch is the culmination of a three-year project between MIT and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, and Technology of Belize. “The Itz’at STEAM Academy represents a revolutionary and bold educational endeavor for us in Belize,” a ministry representative says. “Serving as an institution championing the pedagogy of STEAM through inventive and imaginative methodologies, its primary aim is to push the boundaries of educational norms within our nation.”

Itz’at is one of the first Belizean schools to use competency-based programs and individualized, authentic learning experiences. The Itz’at pedagogical framework was co-created by MIT pK-12 — part of MIT Open Learning — with members of the ministry and the school. The framework’s foundation has three core pillars: social-emotional and cultural learning, transdisciplinary academics, and community engagement.

“The school’s core pillars inform the students’ growth and development by fostering empathy, cultural awareness, strong interpersonal skills, holistic thinking, and a sense of responsibility and civic-mindedness,” says Vice Principal Christine Coc.

Building student confidence and connecting with community

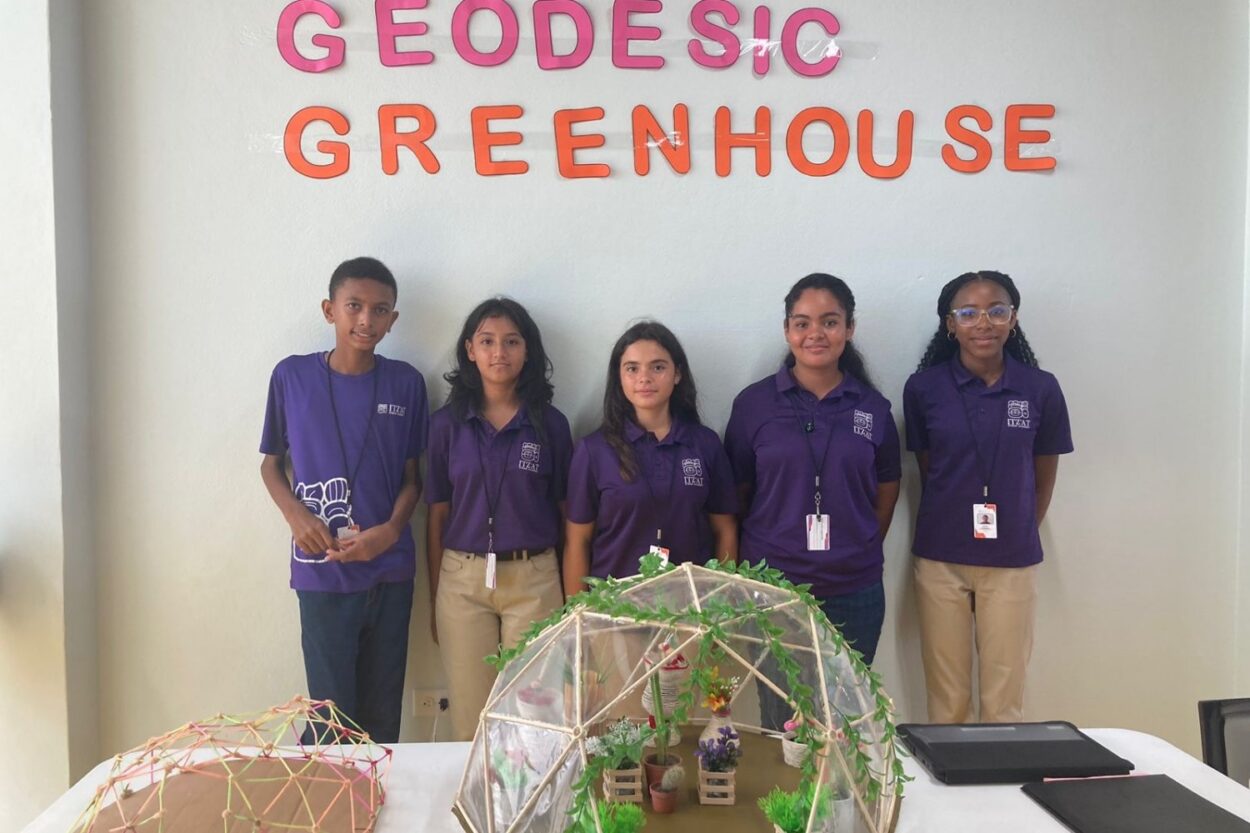

The teaching and learning framework developed for Itz’at is rooted in proven learning science research. A student-centered, hands-on learning approach helps students develop critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills.

“The curriculum places emphasis on fostering student competence and cultivating a culture where it’s acceptable not to have all the answers,” says teacher Lionel Palacio.

Instead of measuring students’ understanding through tests and quizzes, which focus on memorization of content, teachers assess each stage of students’ project-based work. Teachers are reporting increased student engagement and deeper understanding of concepts.

“It’s like night and day,” says Moralez’s father, Alejandro. “I enjoy seeing her happy while working on a project. She’s not too stressed.”

The transdisciplinary approach encourages students to think beyond the boundaries of traditional school subjects. This holistic educational experience reinforces students’ understanding. For example, Moralez first learned about conversions in her Quantitative Reasoning course, and later applied that knowledge to convert centimeters to kilometers for a Belizean Studies project.

Students are also encouraged to consider their roles in and outside of school through community engagement initiatives. Connections with outside organizations like the Belize Zoo and the Belize Institute of Archaeology open avenues for collaboration and mutual growth.

“We have seen a positive impact on students’ confidence and self-esteem as they take on challenges and see the real-world relevance of their learning,” says Coc.

Assignments that engage in real-world problem-solving are practical, offering students insight into future careers. The school aims to create career pathways to strengthen Belize’s existing industries, such as agriculture and food systems, while also supporting the development of new ones, such as cybersecurity.

Students’ sense of belonging is readily apparent to teachers, which positively correlates with their learning. “There’s a noticeable companionship among students, with a willingness to assist one another and an openness to the novel learning approach,” says Palacio.

Parents see the impact of the safe learning environment that Itz’at creates for their children. Izaya Lovell, for example, gets to embrace his whole self. “I get to speak my mother tongue, Kriol,” he says. “I can be like my dad — get dreads and grow out my hair. I can play sports and be physical.”

Izaya’s mother, Odessa Lovell, says her son was a completely different person after one month of studying at Itz’at. “He’s so independent, he’s saving money, and he’s doing things on his own,” she says.

A vision for Belize

The development of Itz’at emerged from a 2019 agreement between MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel World Education Lab (J-WEL) and the ministry for the implementation of a STEAM laboratory school in Belize, with funding from the Inter-American Development Bank. MIT had a proven track record of projects and partnerships that transformed education globally. For example, MIT collaborated with administrators in India, which trained 3,300 teachers to launch a large-scale education system focusing on hands-on learning and competencies in values, citizenship, and professional skills that would prepare Indian students for further academic studies or the workforce. The Belize program is the first time that groups across the Institute have come together to develop a school from the ground up, and MIT pK-12 led the charge.

“One of the key aspects of the project has been the approach to co-design and co-creation of the school,” says Claudia Urrea, principal investigator for the Itz’at project at MIT and senior associate director of MIT pK-12. “This approach has not only allowed us to create a relevant school for the country, but to build the local capacity for innovation to sustain beyond the time of the project.”

Working with an extended team at MIT and stakeholders from the ministry, the school, parents, the community, and businesses, Urrea oversaw the development of the school’s mission, vision, values, governance structure, and internship program. The MIT pK-12 team — Urrea; Emily Glass, senior learning innovation designer; and Joe Diaz, program coordinator — led a collaborative effort on the school’s pedagogical framework and curriculum. Other core MIT team members include Brandon Muramatsu, associate director of special projects at Open Learning, and Judy Perry, director of the MIT Scheller Teacher Education Program, who created operational guidance for finances, policies, and teacher professional development. By sharing insights with J-WEL, the MIT pK-12 team is fueling shared thinking and innovations that improve students’ learning and pathways from early to higher education to the workforce.

Like the students, this is the Belizean teachers’ first experience with project-based learning. The MIT team shared the skills, mindsets, and practical training needed to achieve the school’s core values. The professional development training was designed to build their capacity, so they feel confident teaching this model to students and future educators.

Itz’at currently has 64 students, with plans to reach full capacity of 300 students by 2026. The goal is to continue to build capacity toward STEAM education in the country, expand the possibilities available to students after graduation, and foster a robust school-to-career pipeline.

“The opening of this school marks a pioneering milestone not just within Belize but also across the broader Central American and Caribbean regions,” a ministry spokesperson says. “We are excited about the future of Itz’at STEAM Academy and the success of its students.”