For Mgcini “Keith” Phuthi ’19, spending a summer in Africa was more than a trip back to his home continent after graduation. It was an opportunity to directly impact national policy regarding education in the country of Sierra Leone.

Originally from Zimbabwe, Phuthi, who majored in physics and minored in mechanical engineering, was looking for a particular combination of purposes in his third experience with the MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI): a return to Africa and a chance to explore his passion for education. “I initially thought I would have to choose one or the other, but when I talked to the [MISTI-Africa] program manager about what I could do in Africa, he mentioned the Sierra Leone opportunity.”

Around the world and back again

Ari Jacobovits, the managing director of the MISTI-Africa program, was equally thrilled to match up a student with his ideal project. “What I try to do with every interested student is sit down with them, see what interests them, and build from there. When I met Keith, he obviously had a lot of experience in Africa, being from Zimbabwe, but he also had a particular passion for education,” says Jacobovits. “It’s exciting to facilitate interactions such as Keith’s between the southern region and the western region, thousands of miles apart.”

This was an ideal chance to get hands-on for Phuthi, who often asks himself how to drive higher qualities into educational systems, particularly in regions where science interest and exposure is low. “I felt they could serve as a model for other countries,” he says of Sierra Leone, “and I wanted to be a part of that.”

The mission of the MIT-Africa initiative, an Institute-wide effort, the principles of which help guide MISTI-Africa, is to seek mutually beneficial research, education, and innovation, contributing to economic and intellectual trajectories of African countries, while advancing MIT scholarship and research. “We are always looking to build engagement and collaboration with leading partners and institutions around questions of global import because the solutions to many of the world’s most pressing challenges are found, and will continue to be found, in Africa,” Jacobovits says.

Homeward bound

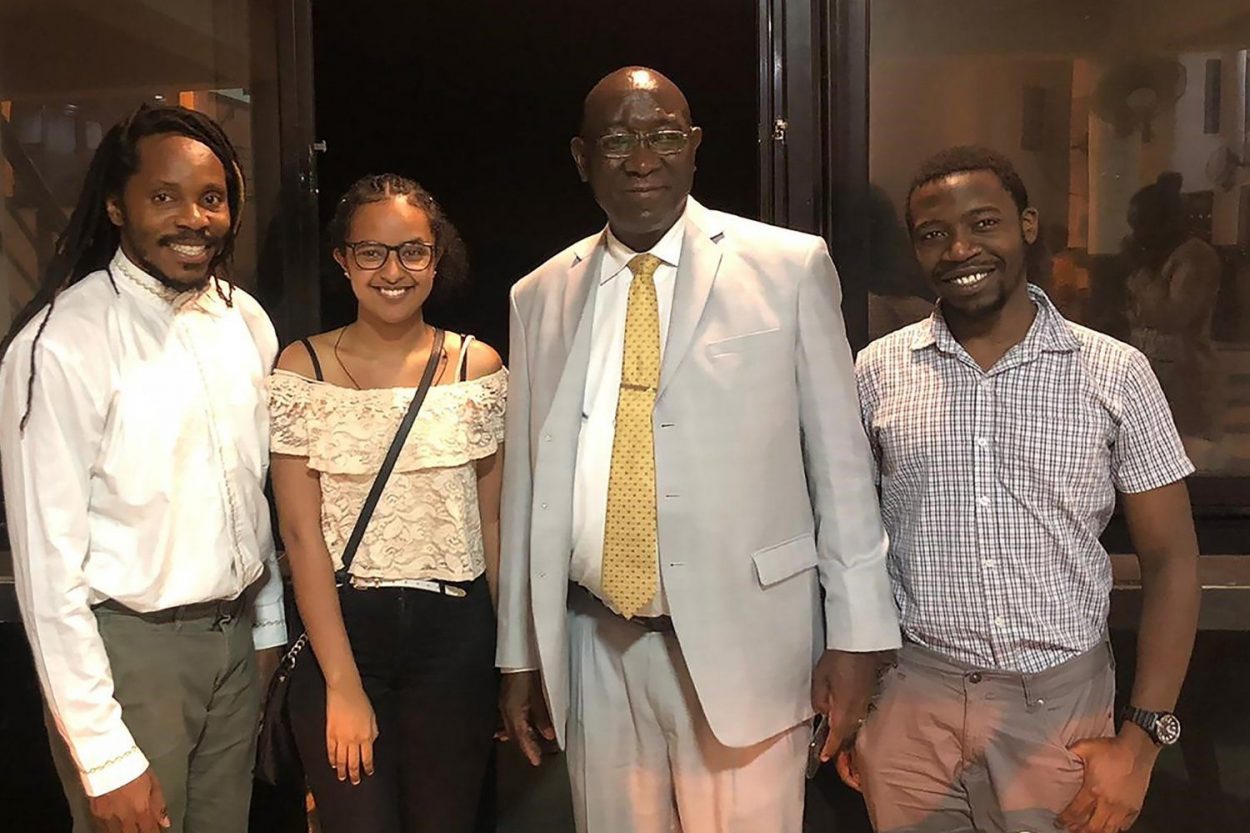

After a visit to MIT by a delegation from Sierra Leone this past March, Phuthi was excited. “A big draw was the incredible ambition and enthusiasm the delegation had,” he says. The delegation included President Julius Maada Bio and an MIT Media Lab alumnus, David Moinina Sengeh SM ’12, PhD ’16, who grew up in Sierra Leone and is now the chief innovation officer for the newly created Directorate of Science, Technology and Innovation (DSTI), uniquely located within the Office of the President in Sierra Leone.

Recently, Sierra Leone’s government has directed significant attention and funding toward science, technology, and innovation. This includes 21 percent of the country’s budget, invested in improving education and lowering the country’s high illiteracy rate — at present, 60 percent of adults in Sierra Leone are unable to read or write. DSTI and the University of Sierra Leone’s Institute of Public Administration and Management went so far as to sign a five-year memorandum of understanding to support this goal. Educational systems are always evolving to better fit the information being taught, but they also need to accommodate the needs of the society they serve. Before any amelioration efforts can be made, the government needs to have a firm understanding of the present, including cataloging education levels, identifying the areas that need attention, and determining the best methods for addressing issues observed.

Education built on education

One project Phuthi helped develop was the national education dashboard for K-12 schooling, one of the first of its kind, he says. The dashboard required cataloging information about the status of education across Sierra Leone. The task called on his experience with data processing and validation pipelines during his physics research in the Laboratory for Nuclear Science under Department of Physics Professor Joseph Formaggio. “This drew a lot on my scientific background in developing metrics, quantifying uncertainties, and building models.”

“But having accurate data wasn’t enough,” Phuthi says. “We needed to use data science and data visualization to develop narratives and models that answer the questions decision-makers might have.” These included complex logistical details such as the route a new government-purchased school bus should take and the optimal locations for the government to build new schools.

To answer these questions, Phuthi also considered other experiences he gained at MIT, such as teaching assistantships and courses in the Education Studies Program, and even conversations he’s had with people from all over the world, including students. It has become a huge benefit to have stepped outside his fields of science and engineering and attend School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences classes in the Teaching Systems Lab. “My hope was to draw on these experiences to help design solutions to improving education in sub-Saharan Africa, and I think I managed to do so,” Phuthi reflects. The progress of DSTI’s current projects can be seen as bar graphs on their website, depicting most as over half complete. The Education Data Hub, the focus of Phuthi’s work, is far enough along to deploy an interactive website for testing.

At the end of the summer, he joined Michel Reda, an electrical engineering and computer science major in her third year, and Hazel Sive, biology professor faculty director of the MIT-Africa program, for a three-day short course. There, he, Reda, and Sive spoke to faculty at Sierra Leone’s Njala University about the best practices for higher education. “It felt like we really got people thinking in the room,” Phuthi says about the forum that generated a report for future policy changes regarding higher education.