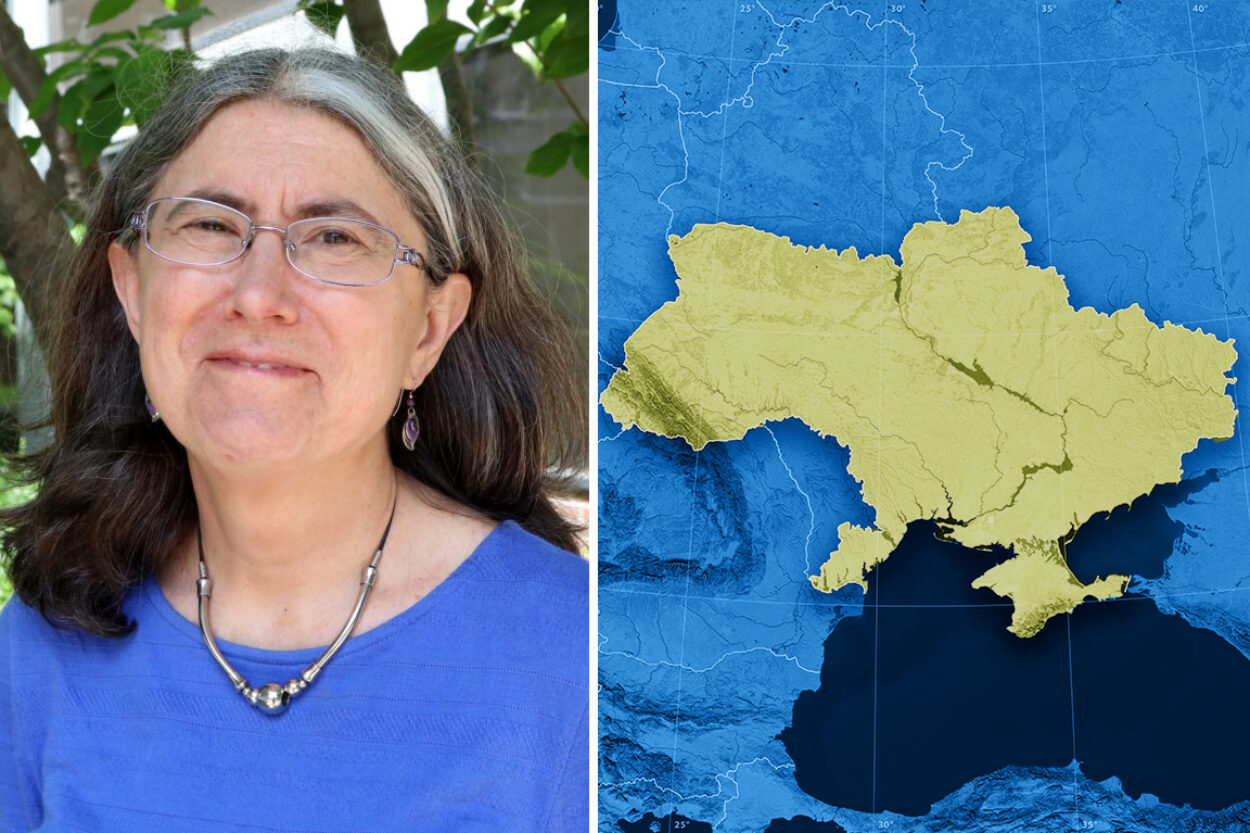

In its first days, Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine in late February has been met with substantial resistance. It has also created civilian casualties, a refugee crisis, a global movement to sanction Russia, and intense concern among observers around the world. MIT News asked Elizabeth Wood, professor of history at MIT and author of the 2016 book “Roots of Russia’s War in Ukraine” (published by the Woodrow Wilson Center and Columbia University Press), to evaluate the situation, as of the beginning of March, slightly less than a week after the invasion began.

Q: What is your overall assessment of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine right now?

A: At this scary moment, with the military conflict in Ukraine changing by the hour, it looks like the Kremlin could win the war but lose the battle for hearts and minds. In war one of the greatest dangers is overconfidence. We ourselves must be careful not to underestimate the Kremlin’s and the Russian military’s ability to dig in their heels and hold out for a long time in Ukraine. This could be a very long, very bloody siege war. At the same time, however, it seems clear that Putin and his small entourage of trusted advisors may have badly miscalculated. Their overconfidence in their own narrative may have blinded them to the realities not only on the ground but also in the entire surrounding region.

Q: Specifically, what are the miscalculations Putin seems to have made?

A: They can be seen in at least three principal areas: in his underestimation of the Ukrainians themselves, in his overestimation of his own playbook, and in his failure to recognize the degree to which other countries and their leaders feel solidarity with the Ukrainians.

Q: What is the nature of his miscalculation regarding the Ukrainian people?

A: Most of what Putin has said recently about Ukraine and Ukrainians was intended to motivate a war he had already decided on. And most of it is too odious to warrant repetition; it should be consigned to Trotsky’s famous dustbin of history. At the core of all Putin’s comments is an idea that is widespread among Russians and repugnant to Ukrainians, namely that Ukraine is “little Russia” and Ukrainians are “little Russians.” Putin has said explicitly that he believes Ukrainians and Russians are “one people” who belong in one state. For him, this is justification for the war. But it is also based on an assumption that the Ukrainians are not capable of effectively and efficiently running their government and deciding their own affairs, including military ones.

Q: What is the “playbook” Putin is using, and how are events unfolding differently than he expected?

A: Putin has used a particular playbook for taking foreign territories quite successfully now for over 20 years: Hit hard and fast with massive force; try for as few civilian casualties as possible; emerge as bloodless and triumphant as possible. He first tried this in Chechnya starting as soon as he was named acting Prime Minister in August 1999, bombing Grozny, the capital city, in October of that year and causing massive civilian deaths, but denying that the Russian intervention was a “war.” Journalists who covered it were killed outright, kidnapped, jailed, and/or banned from publication.

He tried it again in the five-day Georgian War of 2008 when Russian forces were positioned north of the Caucasus Mountains waiting for the slightest provocation from the Georgians in South Ossetia, their northernmost province. In that case they were able to seize South Ossetia and Abkhazia, and both of those republics were declared “independent,” but their residents were granted Russian passports and encouraged to consider themselves citizens of Russia. And he tried it in Crimea, first positioning his own people in the Crimean Parliament and as mayor of Sevastopol’ by coup d’etat, having those leaders ask for Russia’s “help,” declaring Crimea “independent,” and holding a referendum (with Kalashnikovs in every polling place) on Crimea “joining” the Russian Federation.

In 2021-2022, Ukraine presented a challenge, however, probably because of its sheer size. The Russians built up on three and a half sides of Ukraine for almost 11 months before they began the military invasion. The Russian playbook has also relied on divisions within the country they are attacking. This worked in Transnistria, Georgia, Crimea, and in the initial phases of the Donbas takeover. Unfortunately for them, there has been little division between “Russians” and “Ukrainians” in Ukraine. One point Ukrainian scholars have been making repeatedly is that “Ukrainian” has become a civic nationality, more than one of language, religion, or even political identification. Someone can be Ukrainian and speak Russian; they can go to the Russian Orthodox Church or Moscow Patriarchate; they can disagree vehemently about Ukrainian politics. But they agree on their nationhood. Putin has succeeded in uniting Ukrainians in a way that Ukrainians themselves sometimes seem surprised to see.

Q: Finally, how has Putin underestimated the response of so many other countries in the world?

A: Putin seems to have miscalculated that he could hit Ukraine now without serious resistance from the U.S. and Europe. That turned out to be a chimera. Political theater has always been at the core of Putin’s style of rule. His advisers’ reading of Biden was no doubt based on Biden’s public appearances and speeches to the American people, [and assumed] Biden looked weak because of his explicit commitment to building coalitions, trying to make peace among American domestic foes. In the Kremlin’s macho-based view, a peacemaker is by definition weak. What they completely underestimated is the U.S. President’s ability to reach out to world leaders and build some of the ties that the previous president had tried to rip up. The unity that has emerged against Russia is also a sign of the hunger of those world leaders to still work with the U.S.

Another key factor in the unity has been the degree to which leaders at the edges of Russia (Turkey, Finland, Poland, Czechia, Hungary) have taken up support for Ukraine. They have not sat on the sidelines as the Russian leadership no doubt calculated they would. Here Putin’s practices of bullying other leaders may be coming home to roost. He bullied Recep Tayyip Erdogan in 2015-16 for an entire year before finally admitting Turkey back into the fold. He has bullied the Finns for years, to the extent that now they say they wouldn’t wish Finlandization, i.e., living quietly in the shadow of Russia, on their worst enemies. The Central European countries have the most to lose in opposing Putin — they could be next in line. But they have opened their doors to refugees; they have agreed in the decision to eject Russia from [the banking network] SWIFT, a decision that had to be taken unanimously by the 27 E.U. countries.

The leader whom Putin has most underestimated has been Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Often derided as a “TV comedian” who couldn’t possibly know how to lead a country in a major conflict, Zelenskyy has instead shown himself to be an astute, charismatic leader who has been speaking to his people twice a day, rallying them, engaging them, and showing his own fearlessness. Many have criticized him for his allegedly slow response in the build-up of the crisis when he kept urging calm, urging the world not to overreact. But in fact, the Ukrainian military was clearly preparing to rebuff the Russian incursion.

According to media reports, one group for whom Putin’s propaganda does seem to be working is a significant portion of Russians themselves. His control over the internal television media is now so complete that they are not even seeing the war. All media outlets are forbidden from calling the military incursion a “war,” and the authorities are blocking ever more independent media that operate on the Internet, especially the TV station “Rain” and the program “Echo of Moscow.” The “Fortress Russia” mentality that Putin has been building up for the last 10 years is working effectively, so that many (though definitely not all) Russians easily believe the official line that Russia is forced to respond to alleged NATO buildups in Ukraine and “Nazis” who have taken over the Ukrainian government. Harsh penalties for criticizing the war have been introduced, making it “treason” which is punishable by up to 20 years in prison. This makes it unlikely that widespread protests will have much effect on the Kremlin’s decision-making.

With a 40-mile convoy bearing down on Kyiv, it is entirely possible that Russia will crush Ukraine, destroy the land they wanted to annex, and shed massive numbers of Ukrainian lives. They won’t be able to claim the bloodlessness of their supposed victories in Georgia and Crimea. They may be able to suborn and oppress the Belarusian and Russian people as well, through sheer terror tactics. But it seems unlikely that they will be forgiven or understood or respected in the process. Respect has always been what these Russian leaders most want — to be respected on the world stage. Unfortunately, this war has completely undermined any hope of them attaining that respect.